Saturday, January 18 2024, was perhaps the epitome of winter birding in Chicago. Following a very brief warm up, the temperatures were dropping as fast as the cold strong breeze was skimming down Lake Michigan. While it was 25°F (-4°C), a temperature which can feel warm on some winter days, the wind made it feel more more like 2°F (-17°F).1

Still, I was looking forward to birding along the lake. Who knew what kinds of birds those winds would bring down to Park 566? I stepped out of my car and told my friends “it feels like a Kittiwake day,” both because the weather was similar to previous days we’ve seen Black-legged Kittiwakes, and also in an effort to manifest this bird by speaking them into existence (that actually worked once).

There were no Kittiwakes

At least not in this particular stretch of Lake Michigan. There were plenty of American Herring Gulls (Larus smithsonianus) though and they were putting on a show. Dozens upon dozens were piled up along the breakwater at the south end of the park, engaged in a seemingly effortless dance with the wind and waves.

Audio intentionally removed from the clip save your ears from the constant wind.

As I watched them glide above water and ice, I couldn’t help but wonder “how do they not get knocked out of the air by those big waves?” They seemed completely unaffected by what Lake Michigan was throwing at them, occasionally and intentionally dipping down to the water to catch whatever was rising to the surface, and then gliding back up to join their friends.

They too, seemed to be enjoying this day of strong north winds, but were much better suited to it than I was. While I was out there with them, I was covered in layers of wool, fleece, down, and nylon, not to mention a heated vest and heated hand warmers. They were out there just as themselves, having made their own winter gear of down and waterproof feathers.

American Herring Gulls are pretty amazing

It’s hard to fathom that this bird, now a permanent feature of the Great Lakes and Atlantic coasts, was once pushed to the brink of extinction for the sake of fashion in the late 1800s. After protections were put in place their numbers rebounded remarkably well (highlighting their amazing adaptability), to the point that now many think of these lovely large gulls as pests.

They are also brave

Some of my favorite encounters with American Herring Gulls are when they are bravely harassing raptors. I’ve seen them chase after Bald Eagles and Short-eared Owls with vigor, often dangling their pink feet in a questionable show of intimidation.

For some reason they seem to detest Whimbrels

Whimbrels aren’t common here in Chicago so a visit from one during migration causes a lot of excitement. That excitement quickly turns to frustration in birders hoping to spot this rarity, however, as American Herring Gulls ensure Whimbrels’ visits are brief.

Variable and adaptable in almost every sense

As I was reading through the Birds of the World species account and several gull guides, the description of this gull that stuck out the most was “varied.”

Habitat: coastal and near-costal but also inland, along large lakes and reservoirs and also garbage dumps. May nest at altitudes up to 2000 meters, but also in sea-level parking lots. Some breed in the boreal forests, others in large cities.

Food: Basically anything. Fish, mollusks, earthworms, mammals, birds, and berries. Also your picnic lunch and fast-food leftovers.

Behavior: While on land these gulls can walk, run and hop and when airborne they glide, dive, swoop, and flap. On the water they can swim, float, as well as dive, reaching depths up to 2 meters!

Migration: A “complex pattern of variation,” some American Herring Gulls stay where they were born, some migrate only short distances, and some take winter breaks in Bermuda.

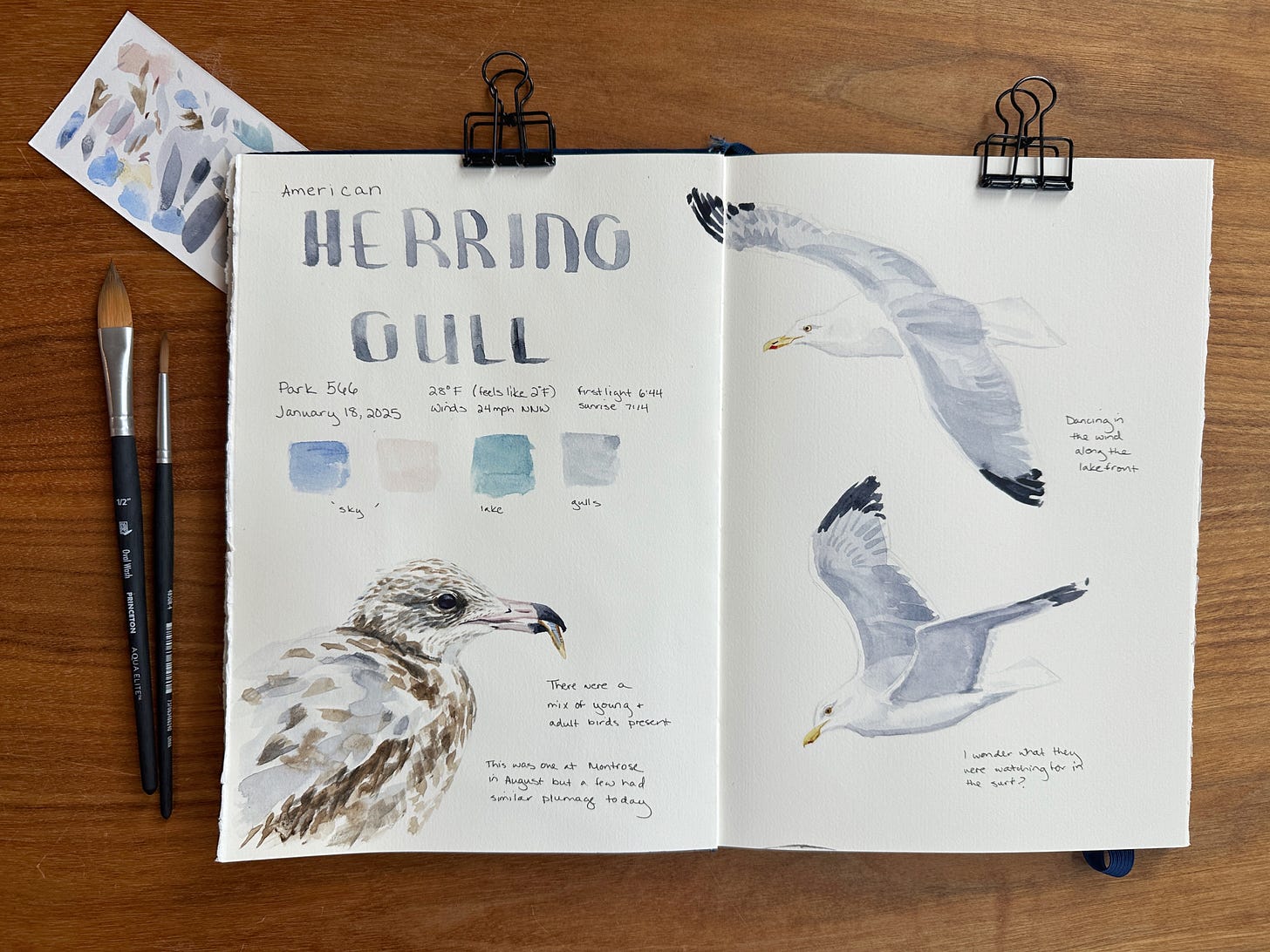

Welcome to my nature journal

To fix this day in my mind, I painted these gulls and the day’s color palette in my nature journal. The gulls in flight were from January 18, the close-up is from a young gull I photographed at Montrose in August. Once I finished the page I was abruptly struck with the thought “did I just paint a young Ring-billed Gull?!”

In the field I use size to differentiate these birds, and that size difference is notable (see photo with the Whimbrel above). I confidently labeled this photo as HERG after taking it in August, and I think I recall it being one of the bigger gulls present, but memories are unreliable historians. And before yesterday I honestly had no idea how closely first cycle Ring-billed Gulls and second cycle American Herring Gulls resembled one another. Before yesterday I honestly never thought I’d used phrases like first and second cycle when referring to gulls. But here we are.

ID challenges

I used to (i.e. before yesterday) use leg color to differentiate Ring-billed Gulls (RBGU) from Herring Gulls (HERG) when size comparisons weren’t available. But first cycle RBGUs have pink legs just like second cycle HERGs do! Bill color? Sibley points out that first cycle RBGU has a pink bill with clean-cut black tip. HERGs? Amar Ayyash advises in The Gull Guide that bills of second cycle HERGs range from mostly black to sharply bi-colored with a black tip. Bill size? RBGUs have a thinner bill while HERGs are larger and broader, as if “stretched from the head like saltwater taffy” as my friend Dan likes to say. Well guess what? Female HERGs are noted to have thinner bills than their male counterparts and Amar notes “bills longer and stronger in some individuals.” Plumage? At this point I’ve read so much about their different plumages that I have no idea what to think. What I do know is that The Gull Guide describes the second cycle HERG’s plumage as “highly variable in every respect” Iris color? This almost convinced me I’d landed on my ID, assuming that only first cycle birds would have dark irises. Wrong again. Second cycle birds of both species have variable iris color, ranging from dark to adult-like yellow.

Stumped

I was completely confused so I sought assistance from birder friends whose ID skills are better than mine. After seeing the photo below, they came back with “second winter Herring.” Once I posed my doubts, each helpfully recanted with “maybe a first winter Ring-billed” now speculating about the bird’s bill size.

From being convinced this bird was an American Herring Gull, to being embarrassed that I’d misidentified a Herring as a Ring-billed (what a rookie!), I’m now back to thinking this bird is a Herring. There’s something about their head shape that looks Herring-ish:

I was also able to dig up this photo from the same day, and I think this may be the same individual near other gulls and the Whimbrel, providing the needed size comparison.

You tell me

This final photo shows the same bird from another angle, so you now have all the information I do. I’ll be eagerly awaiting your comments, ID assistance, and commiseration about the challenges gulls face those of us who like to put birds into neat little boxes. As Pete Dunne writes in Gulls Simplified:

Not every gull encountered in the field is going to be identified, or at least identified correctly. Acceptance of this makes it easier to move forward…

Whatever the consensus, I am delighted that these birds—which I thought I knew so well and encounter almost daily—can still offer so many lessons in beauty, resilience, bravery, and, not least, humility.

Thank you so much for reading! I hope you all have a wonderful week.

💜, Kelly

Images and illustrations: Kelly C. Ballantyne

Sources:

Ayyash, A., 2024. The Gull Guide: North America. Princeton University Press.

Dunne, P. and Karlson, K.T., 2018. Gulls Simplified: A Comparative Approach to Identification. Princeton University Press.

Weseloh, D. V., C. E. Hebert, M. L. Mallory, A. F. Poole, J. C. Ellis, P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2024). American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (B. K. Keeney and S. M. Billerman, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.amhgul1.01

I know Chicago winters are nothing compared to those further north, but still, it was cold.

As you may be tempted to point out, the 4 letter banding code for American Herring Gulls has been updated from HERG to AHGU after the recent species split into American and European Herring Gull. I know this, but HERG was honestly just more natural to type 😉.

I really like that video clip of the gulls hovering in the wind over the water.